In a groundbreaking medical achievement, eight healthy babies have been born in Britain using a pioneering yet controversial reproductive technique that combines DNA from three individuals. It aims to prevent mothers from passing on life-threatening mitochondrial diseases to their children.

These births mark the first detailed outcomes of an experimental method known as mitochondrial donation, a procedure designed to replace faulty mitochondrial DNA — the tiny energy-producing structures in cells — with healthy ones from a donor. The findings were recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine, offering the most comprehensive data to date on the technique’s success.

Why Mitochondrial DNA Matters

While most of our DNA resides in the nucleus of a cell — with genetic material inherited from both mother and father that makes us who we are. But there’s also some DNA outside of the cell’s nucleus, in structures called mitochondria. When this mitochondrial DNA carries harmful mutations, it can lead to devastating conditions in children, such as muscle weakness, developmental delays, seizures, organ failure, and even death.

The mothers involved in this study carried mutations that placed them at high risk of transmitting such disorders to their children.

The Science Behind the Technique

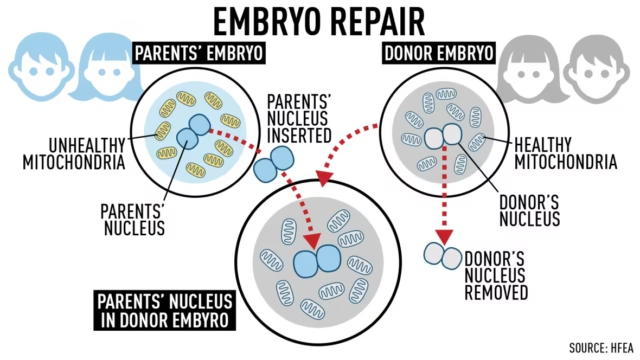

The infants were conceived through mitochondrial donation, a technique that involves transferring the nucleus of a fertilized egg that has faulty mitochondria — cells’ energy factories — into a donor egg cell with healthy mitochondria.

The procedure has been dubbed three-person in vitro fertilization (IVF), because the resulting children carry nuclear DNA from a biological mother and father, alongside mitochondrial DNA from a separate egg donor.

A Global First for the UK

The UK became the first country in the world to explicitly regulate mitochondrial donation in 2015, after more than a decade of research, discussion and debate. Just one UK clinic, the Newcastle Fertility Centre, has been licensed to carry it out by fertility regulator the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA).

Led by reproductive biologist Mary Herbert (now at Monash University, Australia), the Newcastle team treated 22 women carrying disease-causing mitochondria using a mitochondrial donation procedure called pronuclear transfer, leading to eight births (including a pair of twins) and one ongoing pregnancy,

Encouraging Early Outcomes

All eight babies — four girls and four boys — were born healthy and are developing normally. The oldest child is now over two years old, while the youngest is under five months.

While five children have shown no health issues, three experienced minor or treatable conditions:

- One had muscle jerks that resolved on their own

- Another had elevated fat levels in the blood and a heart rhythm issue, both successfully treated

- A third developed a fever from a urinary tract infection

“We’re cautiously optimistic about these results,” said Dr. Robert McFarland, a paediatric neurologist at Newcastle University and co-lead author of the study.

“To see babies born at the end of this is amazing — and to know there’s not going to be mitochondrial disease at the end of that.”

A Solution When Other Options Fall Short

For some women with mitochondrial mutations, pre-implantation genetic testing (PGT) can help identify embryos unlikely to inherit the disease. However, this option is not viable for all, especially those whose eggs consistently contain high levels of faulty mitochondria.

In the Newcastle study, eight of 22 women (36%) undergoing mitochondrial donation conceived successfully, compared to 16 of 39 women (41%) who tried PGT. The reason for this difference isn’t fully understood but may relate to how mitochondrial mutations impact fertility itself.

A Cautious Path Ahead

Although mitochondrial donation has been attempted in other countries — sometimes as an unregulated fertility treatment — the UK remains the only nation with a robust regulatory framework for its use in preventing inherited diseases.

With promising early results, scientists and ethicists agree that continued monitoring and long-term follow-up of these children will be essential to fully understand the safety and efficacy of this revolutionary reproductive technology.